Sommaire

The rise of social media has profoundly transformed human interactions, blurring the lines between private life and professional obligations. In the judicial context, this evolution raises delicate questions about the neutrality and independence of judges. The decision of 5 January 2017 (No. 16-12.394) of the French Court of Cassation illustrates this issue by ruling on the legal qualification of the “friend” link on Facebook. The highest court emphasised that such a virtual link, often created without any significant interaction, cannot automatically be equated with a genuine friendship. This clarification marks an important step in adapting case law to the realities of the digital age.

The distinction between virtual and real friendship

Facebook “friend”: a symbolic link, not presumed to be close

The Court of Cassation held that the term “friend” as used on Facebook reflects the platform’s own terminology rather than a traditional social recognition. In many cases, such a connection results from algorithms, professional contacts, or weak ties, without genuine personal involvement. A virtual connection therefore does not, in itself, indicate emotional closeness or influence. This position ends the automatic conflation of digital and personal relationships. It also reminds us that the law must take into account the specific practices of each digital environment.

No automatic presumption of bias

The decision confirms that a “friend” link on a social network is not, on its own, sufficient grounds to recuse a judge. Without factual evidence of a personal relationship or partiality, bias cannot be established. This stance protects the freedom to use social media while maintaining a high evidentiary standard. It thus strikes a balance between safeguarding the image of justice and acknowledging common digital practices. The Court reaffirmed that only concrete evidence can justify challenging a judge’s impartiality.

Concrete elements that may demonstrate bias

Evidence required by case law

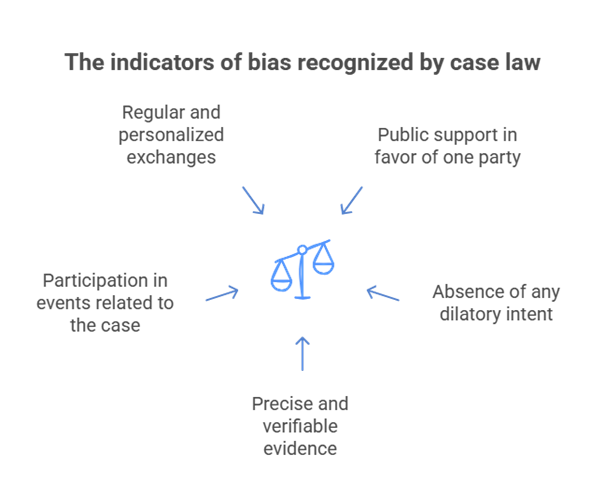

For a recusal request to succeed, it is essential to provide tangible evidence. Such evidence may include:

- Frequent and personalized exchanges between the judge and the party.

- Public expressions of support or positions taken in favor of one party.

- Joint participation in events directly related to the case.

- Precise, verifiable evidence directly linked to the dispute.

- Elements ensuring that recusal is not used as a dilatory or strategic tool without any objective basis.

Probative value and legal requirements

The elements presented must demonstrate an objective appearance of bias, as it would be perceived by a reasonable observer. The criteria include:

- Rejection of isolated or anecdotal evidence (for example, a single screenshot or a one-off connection).

- The need to establish an overall context and a significant frequency of interactions.

- Consideration of consistent indicators demonstrating an objective risk of bias.

- A rigorous factual approach, excluding purely subjective interpretations.

- Ensuring legal certainty and the stability of rendered decisions.

Recognition of digital realities

In ruling this way, the Court acknowledges the widespread use of social media and the connections they generate. Digital relationships can exist without implying a real personal bond, and their mere existence does not inherently threaten impartiality. This recognition marks progress in adapting the law to the digital era.

Freedom of use framed by ethical prudence

However, the decision does not exempt judges from their ethical obligations. Their online presence must remain compatible with the requirements of neutrality and restraint. Any interaction likely to create an appearance of bias should be avoided to maintain public confidence in the judiciary.

Implications for public perception of justice

A reassuring decision for judicial neutrality

By requiring concrete proof of bias, the Court reinforces confidence in the independence of judges. This stance reassures that objective criteria, rather than mere appearances, guide the assessment of impartiality.

Risks of negative public perception

Nevertheless, part of the public, unfamiliar with legal nuances, may view these virtual links as a potential source of conflict of interest. This calls on judges and judicial institutions to educate the public about the real significance of such digital connections.

Conclusion

The decision of 5 January 2017 is a cornerstone in defining judicial impartiality in the digital age. It makes clear that the mere existence of a virtual link cannot undermine a judge’s neutrality, absent tangible proof of closeness or influence. This ruling helps to stabilise case law on recusal while providing a clear framework for legal practitioners.

Dreyfus Law firm is part of a global network of lawyers specialising in Intellectual Property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the assistance of the entire Dreyfus team.

FAQ

Can a judge be Facebook friends with a party to a case ?

Yes, but this link alone does not justify recusal.

What evidence can prove bias ?

Frequent exchanges, public support, or direct involvement in the case.

Does the private nature of exchanges affect the analysis ?

No, only proof of a concrete relationship matters.

Does this rule apply to LinkedIn or Instagram ?

Yes, it applies to all social networks.

Can a judge be sanctioned for online activities ?

Yes, in cases of breach of neutrality or restraint obligations.