The Data Protection Act: Key Changes Since the Adoption of the GDPR

Introduction

The Data Protection Act (Loi Informatique et Libertés), of January 6, 1978, has since then evolved to meet the new challenges posed by digital technologies and the management of personal data.

The successive reforms, particularly with the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the EU Directive 2016/680’s transposal, and recent amendments, have allowed the law to adapt to contemporary issues.

This article explores the major changes to this legislation and analyzes their impact on personal data protection in France.

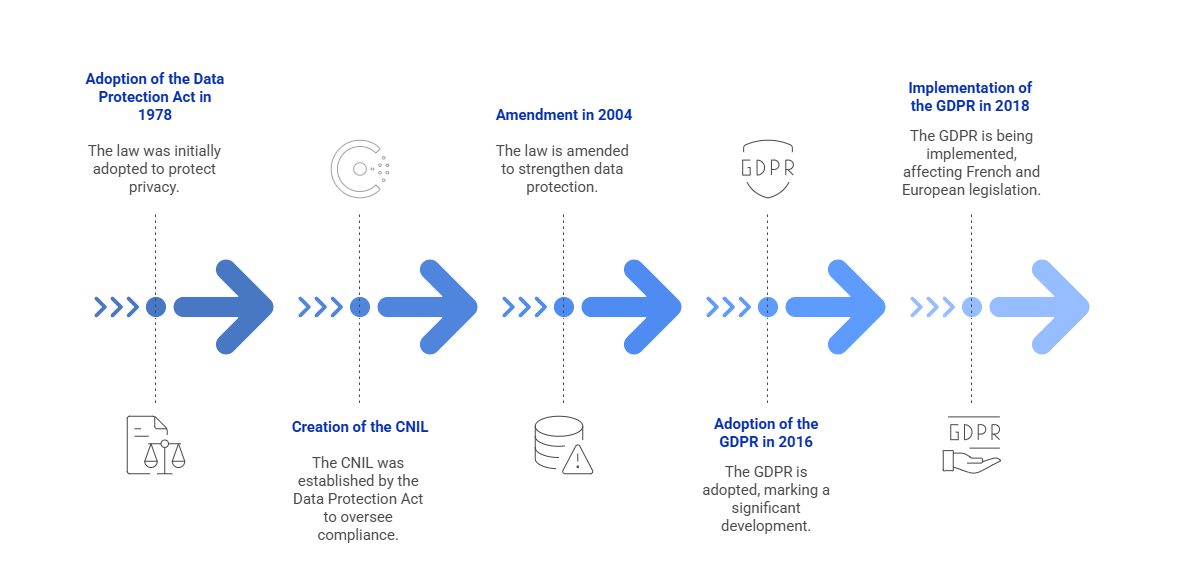

The origin and evolution of the data protection Act

The Data Protection Act was initially adopted in 1978 to protect citizens’ privacy in the context of personal data management. This law established the Commission Nationale Informatique & Libertés (CNIL), French independent administrative authority, to ensure that data processing practices comply with the law’s fundamental principles. The original law aimed to regulate the collection and processing of personal data by both public and private sectors and has been amended twice:

• In 2004, with the introduction of new provisions to strengthen data protection, notably through the transposal of the European Directive 95/46/EC, which implemented adjustments to the law.

• In 2016, with the adoption of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in May, which came into effect in 2018, marking a significant evolution in both French and European legislation.

Major changes brought by the GDPR

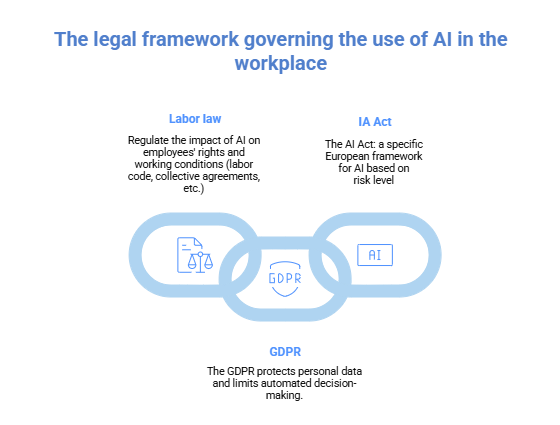

The GDPR had a significant impact on the Data Protection Act by strengthening personal data protection and harmonizing rules at the European level. While it is not directly a modification of French law, its application forced national legislation to integrate its core principles.

The GDPR has enabled to guarantee :

• The right to clear and accessible information when collecting data.

• The right to access, rectify, and erase (right to be forgotten).

• Data portability from one service to another.

The GDPR also expanded the CNIL’s powers in terms of enforcement, allowing fines up to 4% of a company’s global turnover for non-compliance. The CNIL now plays a more proactive role in monitoring corporate compliance.

Relationship between national law and the GDPR

The Data Protection Act continues to play a complementary role to the GDPR on issues where the European regulation allows for national discretion.

For example:

• The processing of health data, offense-related data, or journalistic data.

• Criminal law files, governed by specific rules derived from the European directive introduced alongside the GDPR.

These provisions allow the legal framework to adapt to areas where security and protection concerns are particularly high.

The evolution of the Data Protection Act remains dynamic, with regular amendments, notably decrees published since 2018, specifying the operational modalities of the new rules.

New obligations for businesses

The Data Protection Act, as amended by the GDPR, now imposes additional obligations on businesses regarding the management of personal data:

• Appointment of a Data Protection Officer (DPO):

Certain businesses must appoint a DPO to ensure that data processing practices comply with the legislation.

• Explicit and Documented Consent:

Businesses must obtain explicit consent from users before collecting their data, and this consent must be documented and easily accessible.

• Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA):

Businesses must conduct PIAs when data processing presents a high risk to individuals’ rights and freedoms, especially in the case of automated processing.

Challenges of data protection in the digital Age

1) The rise of Big Data and AI

The massive processing of data (Big Data) and the growing use of artificial intelligence (AI) in personal data processing pose new challenges. Businesses must now justify the necessity of collecting data and can no longer rely on a lax approach.

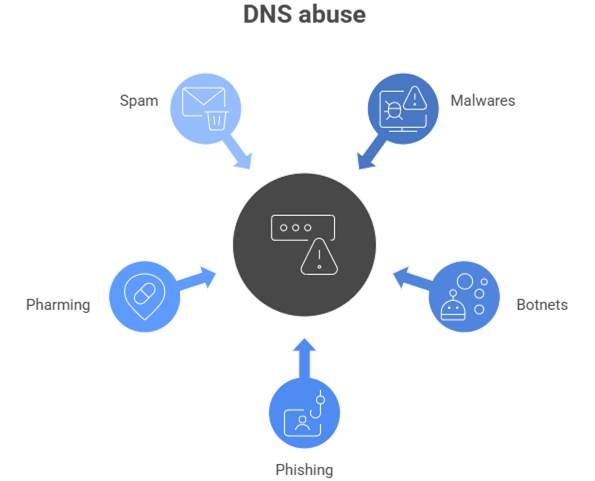

2) The risks of data breaches

Despite efforts to strengthen security, data breaches remain frequent. Companies must not only take preventive measures but also be prepared to notify competent authorities and affected individuals in case of a data breach.

3) International Data Transfers

The transfer of data outside the European Union is strictly regulated. Businesses must implement appropriate mechanisms, such as standard contractual clauses or comply with adequacy regulations (e.g., the Privacy Shield for transfers to the United States), to ensure the security of personal data.

Conclusion

The Data Protection Act, as amended by the GDPR, represents a strengthened legal framework for personal data protection, particularly in the context of rapid technological advancements. Businesses must comply with these new rules, not only to avoid penalties but also to ensure the trust of their users.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Dreyfus & Associés works in partnership with a global network of specialized intellectual property lawyers.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team.

Q&A

1.How does the GDPR affect companies that process sensitive data?

Companies that process sensitive data must implement enhanced security measures and obtain explicit consent from the individuals concerned. They must also conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) to assess the risks associated with these processing activities.

2.Which companies must appoint a DPO?

Companies that process personal data on a large scale or sensitive data must appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO). It is also mandatory for public organizations and those involved in regular monitoring of individuals.

3.What are the risks for companies in case of non-compliance?

In case of non-compliance, companies risk financial penalties of up to 4% of their global turnover or €20 million, depending on the severity of the violation. They may also face legal action and damage to their reputation.

4.How can companies ensure the security of personal data?

Companies must implement technical and organizational security measures, such as data encryption, strict access controls, and continuous training for employees on security best practices.

5.What is a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)?

A Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) allows companies to analyze the risks to data protection before launching processing activities that may affect individuals’ privacy. It is mandatory for high-risk processing, particularly in cases of large-scale surveillance.

6.Is user consent always necessary for the processing of their data?

Explicit consent is required when data is processed based on this consent. However, in certain cases (e.g., for contract execution or legal obligations), other legal bases, such as legitimate interest, can be used without the need for prior consent.

This publication is intended for general public guidance and to highlight issues. It is not intended to apply to specific circumstances or to constitute legal advice.