Sound trademarks: what protection opportunities?

Introduction

In the field of intellectual property, sound trademarks have become a powerful differentiating tool for businesses. Protecting a sound as a trademark offers many unique opportunities for businesses seeking to secure their identity. This article explores the strategic advantages, legal considerations, and best practices related to the protection of sound trademarks.

What is a sound trademark?

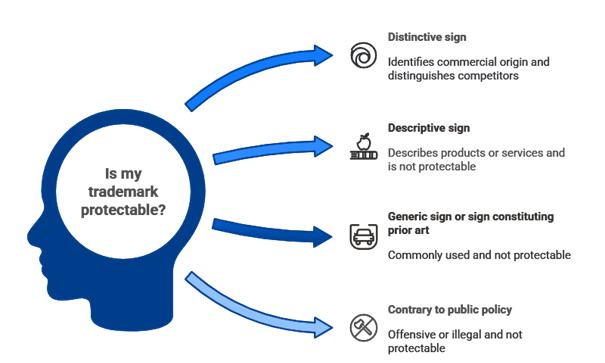

Since December 15, 2019, it’s possible to register an MP3 file as a trademark with the INPI. A sound trademark is a trademark consisting of a sound or a combination of sounds. To be registered, the sound trademark must comply with the existing validity requirements in trademark law. IP Offices often emphasize the importance of distinctiveness when registering a sound trademark.

According to the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), in order for a sound to be protected as a trademark, it must be distinctive and capable of distinguishing the products or services of one company from those of others

This criterion implies that the sound must be unique, non-functional, and directly associated with the brand’s identity. For example, a jingle or a specific sound effect used in advertisements can be registered as a trademark.

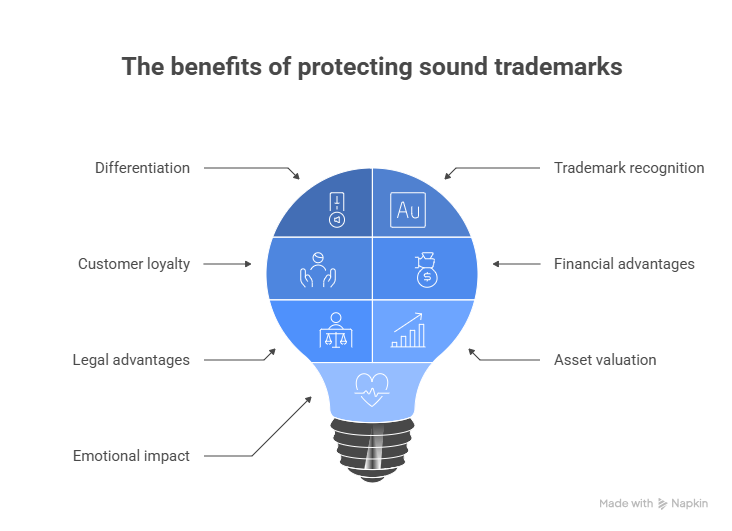

The benefits of protecting a sound trademark

Sound trademarks help create a distinct identity for a company, thereby differentiating it from its competitors.

Examples of registered sound trademarks:

These sounds are closely associated with the undertaking from which they originate, representing a powerful lever for fostering brand loyalty and public recognition.

By registering a sound trademark, companies can license it for use in various media, advertisements, and products, generating new revenue streams while protecting their intellectual property from unauthorized use (legal action for infringement could then be pursued). Therefore, the sound trademark represents a significant and valuable asset for a company.

The legal framework for sound trademarks

Several landmark cases have established the legal precedent for sound trademarks. A notable example is the EUIPO’s refusal to register the jingle of Netflix after several attempts

As the sound is too short and too simple, it would not be sufficiently distinctive in the mind of the relevant public. In other words, consumers would not automatically perceive this sound as a distinctive sign linked to Netflix. However, the company succeeded in registering its jingle as a multimedia trademark, combining both its logo and jingle, as well as the term “TUDUM” as a word trademark.

However, a decision handed down by the General Court of Justice of the European Union on September 10, 2025, appears to point towards a more favourable assessment of the registrability of sound marks.

In this case, a Berlin public transport company sought the registration, as a European Union sound trademark, of a two-second jingle composed of four notes.

The application was rejected by the EUIPO, and then by its Board of Appeal, on the grounds that the sign was too short and too simple to be perceived as a trademark by the relevant public.

In its ruling, the Court annulled the decision of the Board of Appeal and held that the disputed jingle was eligible for registration as a European Union trademark.

He first considers that the requirement for a sign to “differ from the norms and practices of the sector,” often applied to figurative marks, does not apply to sound marks, which constitutes a favorable decision.

The Court further highlighted that only a minimal degree of distinctiveness is required. In this case, several factors favored the registrability of the jingle: its brevity, which aids in memorization, its structure composed of successively distinct sounds, its originality, and, most importantly, the fact that it does not reproduce a sound directly related to the execution of the transport service.

It also appears that the fact a sound serves a practical function, such as attracting the attention of passengers, does not prevent it from simultaneously functioning as a trademark. The Court thus recognizes that a sound sign can be both functional and distinctive, as long as it is perceived by the public as an indicator of commercial origin.

This ruling represents a notable relaxation in the assessment of the distinctiveness of sound marks. Unless overturned in the future, it serves as a favorable signal for trademark holders wishing to protect sound identities within the European Union.

Best practices for protecting your sound trademark

When choosing a sound to protect as a trademark, it is essential to select a sound that is memorable, distinctive, and consistent with the brand’s image. It is advisable to consult intellectual property experts to ensure that the sound is both effective and protectable.

The registration process involves selecting the appropriate intellectual property office (INPI, EUIPO, USPTO) depending on the desired scope of protection, submitting the sound file, and verifying that it meets all the necessary legal criteria for registration. Seeking advice from experts throughout this process can significantly enhance the likelihood of a successful registration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, protecting a sound as a trademark offers numerous strategic advantages in today’s competitive market. By securing the legal protection of a distinctive sound, businesses can enhance the visibility, recognition, and profitability of their brand.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team.

FAQ

1. What types of sounds can be registered as a trademark?

Any type of sound can be registered as a trademark if it is distinctive and non-functional.

2. How long does it take to register a sound trademark?

The registration process for a sound trademark can take several months, depending on the IP office and whether objections are raised.

3. Can I use a sound trademark in different countries?

Yes, it is possible to protect a sound trademark internationally through systems like the Madrid Protocol, which allows for global trademark protection.

4. What are the costs of registering a sound trademark?

Costs vary depending on the jurisdiction, and may be substantially higher if you opt for additional services such as legal consultation.

5. How can the evidence of unauthorized use of a sound trademark be proven?

To prove the unauthorized use of a sound trademark, it is necessary to gather concrete elements showing that the sound is being used without authorization: audio recordings, screenshots of advertisements, websites, or products using the sound trademark. It is also possible to use media monitoring tools or online platforms to detect unauthorized use.

This publication is intended for general public guidance and to highlight issues. It is not intended to apply to specific circumstances or to constitute legal advice.