Complete Guide on Bad Faith in Trademark Cancellation Proceedings before the INPI

Introduction

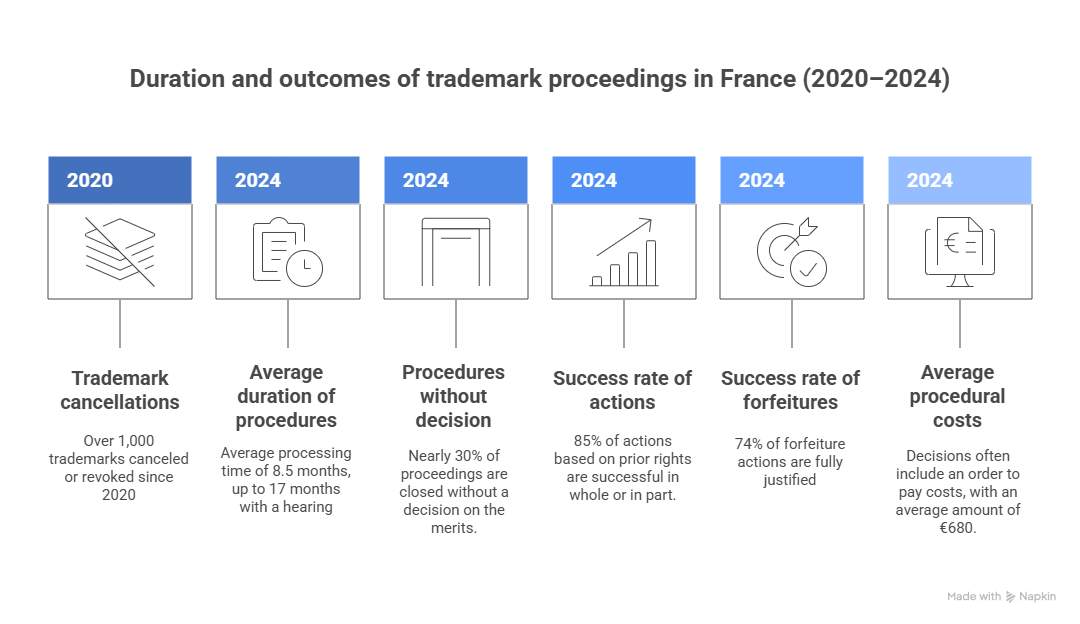

The administrative cancellation procedure has been available before the INPI since April 1, 2020, thanks to the PACTE Law of May 22, 2019. After five years, this procedure has proven highly successful. Bad faith in the filing of a trademark is one of the most frequently invoked absolute grounds for cancellation before the INPI. The rise of parasitic strategies, increased competitive tensions, and the consolidated case law from the CJEU have prompted companies to examine what this concept actually entails.

In this article, we provide a comprehensive guide to understanding and identifying bad faith in a trademark application, in order to determine under which conditions a nullity action can be brought before the INPI.

Understanding the concept of bad faith in trademark law

Legal definition and foundations

Article L.711-2 11° of the French Intellectual Property Code provides that a trademark filed in bad faith cannot be validly registered. If it is nevertheless registered, it may be declared null.

More specifically, the prohibition of bad faith targets any filing made with an intention contrary to honest commercial practices, whether to harm a competitor, unduly monopolize a sign, or divert the essential function of indicating origin.

Presumption of good faith and burden of proof

Under Article 2274 of the French Civil Code, good faith is always presumed. The burden of proof lies with the claimant seeking nullity, who must provide relevant and consistent evidence. This evidence must be dated, contextualized, and allow assessment of the applicant’s intention at the time of filing.

Identifying bad faith in a trademark application

Fraudulent behaviors targeting a specific third party

This category covers situations in which the applicant knew of prior use and filed with the intention of harming the third party’s interests, for example:

- Filing a sign used by a former business partner, employee, or distributor

In the Secretum decision of April 15, 2025 (NL24-0093), a commercial partnership existed between the claimant and the owner of the contested trademark. The claimant had created a wine trademark specifically for the owner, with a contract explicitly stating that the trademark remained the claimant’s property. Despite this clause, the owner filed an identical trademark, reproducing both the term and the calligraphy.

- Intent to improperly benefit from the reputation of the sign

For example, in a July 3, 2023 decision (NL23-000) regarding the trademark “” (or “BANDE DE FILS DE SNAP”) the INPI considered that the trademark exploited the notoriety of the signs “SNAPCHAT” and “

”. The contested trademark was filed with the intent to create an association in the public’s mind and profit from the reputation and success of the existing application.

- Coincidence of the end of a contractual relationship and a targeted filing

In the HYGROTOP decision of February 23, 2022 (NL21-0167), the claimant had ended commercial relations with the company distributing and installing its products. On the same day, the managing director of the distributing company filed the claimant’s name as a trademark.

Filings diverting the essential function of a trademark

Some fraudulent filings do not target a specific third party but aim to obtain an unjustified monopoly, for example:

- Filing to prevent a revocation action

In the Pomone decision of March 27, 2025 (NL23-0276), the claimant requested that the owner of preexisting POMONE marks (filed in 2017 and registered for more than five years) provide proofs of use, according to the rules controlling use of older marks. Less than three weeks after this request, the owner filed the contested trademark to strengthen its position in negotiations regarding the purchase of the marks.

- Filing a work in the public domain

In the Pompon decision of September 13, 2024 (NL23-0183), the trademark «POMPON», filed by a museum shop operator, was challenged by Dixit Arte SAS. The claimant argued that the registration aimed to monopolize the name «Pompon», associated with sculptor François Pompon, whose works are in the public domain.

For more information on this matter, please refer to our previously published article.

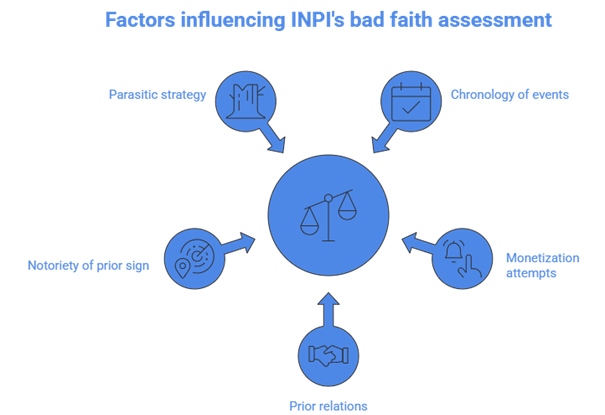

Factual indicators considered by the INPI

The assessment is global and depends on multiple factors, such as:

Chronology of events (often decisive), e.g., in Drag Race France, April 26, 2023 (NL22-0205), the contested trademark was filed simultaneously with the announcement of the show’s arrival in France by the claimant.

Attempts to monetize the filing, e.g., in Google, August 30, 2021 (NL21-0055), the owner of the contested marks offered to modify the project in exchange for compensation, indicating a “wait for a monetary proposal.”

Other factors include:

- Prior relations between the parties;

- Notoriety of the prior sign;

- A clearly parasitic strategy of multiple filings.

Conversely, the INPI rejects bad faith when a filing aims to strengthen preexisting rights or involves a real and legitimate exploitation project.

Bad faith as a procedural tool before the INPI: the example of forfeiture through acquiescence

Article L.716-2-8 of the French Intellectual Property Code provides that the holder of an earlier right who tolerated the use of a later-registered trademark for five consecutive years cannot request nullity of that later trademark. This is known as forfeiture through acquiescence.

However, the article makes an exception: nullity is still possible if the registration was filed in bad faith. This serves as a powerful lever when the prior right holder discovers an abusive filing late.

In the recent LOCPLUS decision of December 14, 2023 (NL21-0255), the issue was examined, showing the strictness required to overturn forfeiture. In that case, although bad faith was invoked to bypass forfeiture, the argument was rejected due to insufficient evidence.

Conclusion

Cancellation of a trademark for bad faith in INPI proceedings is a decisive legal mechanism to combat parasitic strategies. Rigorous assessment of bad faith strengthens the legal certainty for economic actors.

In an environment of increasing trademark conflicts, understanding this absolute ground for cancellation is essential to protect intangible assets and anticipate litigation risks.

Dreyfus & Associés assists its clients in managing complex intellectual property cases, offering personalized advice and comprehensive operational support for the complete protection of intellectual property.

Nathalie Dreyfus with the support of the entire Dreyfus team

FAQ

1. Can the INPI raise bad faith ex officio during examination of a trademark application

No. The INPI cannot raise bad faith on its own; it can only be invoked by a third party in a nullity action.

2. Is likelihood of confusion required to prove bad faith?

No. Bad faith sanctions a fraudulent intention, independent of confusion analysis.

3. Can a company file a name it plans to commercialize later?

Yes, provided there is a genuine and fair intention to use it, not as part of a fraudulent strategy to block a competitor.

4. Can multiple filings indicate bad faith?

Yes, if they reveal a systematic strategy to capture signs used by third parties.

5. Can bad faith exist without targeting a third party?

Yes, for example, when the filing diverts the essential function of a trademark.

This publication provides general guidance and highlights key issues. It is not intended for specific cases nor to constitute legal advice.