Generative AI: Balancing Innovation and Intellectual Property Rights Protection

Introduction

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) generally refers to a scientific discipline. According to the European Parliament, artificial intelligence (AI) is a tool that machines use to simulate human-like behaviours such as reasoning, planning, and creativity (1). One key feature of AI is machine learning, which allows it to learn from its own experiences, giving it autonomy.

The introduction and rapid development of generative AI in the legal industry have raised concerns among legal professionals. Currently, these generative AIs are capable of producing creative works based on user instructions and collected data. Given the widespread use of these technologies in professional settings, the legal implications, particularly those relating to copyright law, raise concerns.

The use of generative AI and copyright

The use of generative AIs such as ChatGPT (dialogue generator) or Midjourney (image generator) raises concerns about how copyright law applies to the generated content. It is necessary to establish who is entitled to ownership of the content produced in this manner and whether it qualifies for copyright protection. ChatGPT is an advanced language model developed by OpenAI. It uses a deep learning algorithm known as GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) to generate human-like responses to text inputs.

Should we expect copyright protection for AI-generated works?

The framework for protecting works of mind is laid out in Article L.112-1 of the Intellectual Property Code, which specifies that an item must be a formalised and original intellectual creation in order to be protected.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has evolved the definition of originality over time to reflect advancements in technology and digital media. Taking a more objective approach in the Infopaq (2) case in 2009, the CJEU defined originality as “an intellectual creation that is an expression of the author’s own intellectual creation.” In addition, the CJEU does not rule out the possibility that a work can be considered original even if it was influenced by technical factors during its creation (3).

The CJEU has also confirmed that it is possible to create original works by involving a machine or device in the creative process (4). In this case, it did not involve AI but photography, a domain that was long considered by scholars to not be eligible for copyright protection due to the mechanical nature of the creation process.

Therefore, not all works involving the contribution of AI can be considered original under the current understanding of originality in positive law. To what extent the user has participated in the creative process is a balancing act that must be performed to determine whether or not the work can be considered original.

Several cases illustrate the international dimension of these questions, sometimes reaching different conclusions. For example, in a dispute between Tencent and Shanghai Yingxun Technology (5), the Chinese court ruled in favour of copyright protection for a work generated using an algorithmic programme. This decision supports the extension of copyright protection to works generated by AI. On the contrary, the United States Copyright Office confirmed on February 21, 2023 (6), the absence of copyright protection for images produced using the AI Midjourney, concerning the comic book “Zarya of the Dawn ” by New York artist Kris Kashtanova.

Ownership of AI-generated content

Copyright law protects the intellectual creations of individuals. It grants authors the right to express themselves through their works and recognises their awareness and intent during the creative process. It is clear at this time that AI does not currently have these specific qualities.

AI is not recognised as an author in the current legal framework, and according to existing copyright laws, the attribution of authorship is reserved for humans who can be identified as the creators of the work produced by AI. These individuals are acknowledged as authors based on their influence on the outcome and their active participation in the creative process.

The jurisprudence, both at the European and French levels, has not yet pronounced on the question of who, between the user and/or the AI developer, will hold the rights to an original work created using AI. However, the terms of service of OpenAI (the developer of ChatGPT) state that the rights to the content belong to the users. This contradiction highlights the urgent and definitive need to address these questions.

There are several hypotheses currently under consideration to ensure the adequate protection of AI and its development. These include exploring potential changes to copyright law, such as redefining the originality requirement or even establishing a framework dedicated specifically for AI.

The High Committee for Literary and Artistic Property (CSPLA) released a report (7) that examines various viewpoints on copyright ownership while delving into the fields of artificial intelligence and culture. The report explores copyright ownership in relation to artificial intelligence and culture and suggests adopting an English law-based model that establishes specific regulations for “computer-generated works.” The aim is to address the implications of these concepts and provide clarity within copyright frameworks.

Copyright infringements and generated AI content

Since works generated by AI often rely on existing content, there is a possibility that they could constitute infringements of copyright. The absence of mention of the sources used by ChatGPT to generate content illustrates the risk of infringement of third-party rights.

The ongoing legal conflict involving photographer Robert Kneschke and AI entity LAION has raised concerns regarding potential copyright infringements. Kneschke uncovered that some of his photographs were present in LAION’s database and promptly requested their removal. The case has been escalated to the District Court of Hamburg, making the progress of this case worth monitoring.

It is important to note that many AI systems do not provide guarantees regarding the absence of infringement of third-party rights in the generated outputs. As a result, users are advised to refer to the terms of use of the specific AI system to understand the responsibilities and liabilities related to copyright and potential infringement issues.

If the rights holders of the collected data find that their rights are violated, they have the option to pursue legal action based on infringement or unfair competition. This highlights the necessity for a distinct framework governing the use of AI, as demonstrated by OpenAI, which already outlines in its terms of service that users are responsible for their use of the tool and must ensure that it does not infringe upon the rights of third parties.

Risks Related to Result Reliability, Privacy, and Right to Image

The use of AI carries additional risks beyond copyright infringement. The reliability of the generated results can be a concern, as can the potential risks to privacy and the right to an individual’s image. In the case of AI-generated content, such as ChatGPT, the results may contain inaccurate, discriminatory, or unjust information. However, according to the European Parliament, AI-generated content cannot be classified as “Your Money Your Life” (YMYL) content, but verifications should still be performed.

At the same time, the European Union is currently considering legal initiatives to regulate AI systems, such as the European Commission’s proposed AI Act (8) regulation and two directive proposals published on April 21, 2021, and September 28, 2022. These legislative frameworks aim to address the issue of civil liability for AI systems.

AI’s use of personal and confidential information

The malfunction of ChatGPT that resulted in a data leak in March 2023 illustrates the challenges related to data confidentiality. Similarly, a study by security publisher Cyberhaven, as reported by “Le Monde Informatique (9),” raised concerns about the dangers connected with employees using ChatGPT. The study highlighted the risks of data leaks by employees, including sensitive project files, client data, source code, or confidential information.

In order to operate as intended, conversational agents like ChatGPT use and collect data, although they are not specifically designed for personal data collection. The nature of the collected data needs to be examined to determine whether it is protected or not. If the data is protected, the developer of the AI has an obligation to seek permission from the data rights holders.

Some countries adopt a cautious position regarding the processing of personal data by ChatGPT. In Canada, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner has initiated an investigation against OpenAI (10). In Italy, the President of the Italian Data Protection Authority, GPDP, temporarily banned access to ChatGPT on March 31, 2023 (11), accusing it, among other things, of not complying with European regulations and lacking a system to verify the user age. Since then, modifications have been made, and ChatGPT is available again in Italy.

Indeed, OpenAI’s privacy policy does not appear to comply with the requirements of the GDPR and the Data Protection Act, particularly regarding the absence of information about the retention period of processed data.

The National Commission for Informatics and Liberties (CNIL) published guidelines in 2021 to ensure that Chatbots respect individuals’ rights (12). It also issued guidelines and recommendations in 2021 (13) on the use of cookies and other trackers governed by Article 82 of the Data Protection Act (14) (transposition of Article 5.3 of Directive 2002/58/EC “ePrivacy” (15)).

The goal of these recommendations and guidelines is to ensure informed consent from users and provide transparency about trackers. The CNIL also has the power to impose sanctions in cases of non-compliance by relevant actors. It is crucial for the involved parties to ensure adherence to the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the ePrivacy Directive.

These potential legal hurdles must be considered if we are to make ethical and responsible use of this technology, and concerns such as copyright infringement, data collection, and ownership must be carefully considered by all parties involved in the creation and use of AI.

The Current Legal Framework of AI and Future Perspectives

The European Union intends to establish an artificial intelligence regulatory framework. In 2020, the European Parliament passed resolutions on artificial intelligence and its applications (17), and new European proposals aim to ensure the smooth operation of the internal market. The goal is to make the Union a world leader in developing ethical and trustworthy AI that protects ethical principles, such as fundamental rights and Union values.

The European Regulation Proposal: “AI Act”

On April 21, 2021, the European Commission proposed new rules to set uniform rules (18) for the commercial release, deployment, and use of artificial intelligence. The legislative process is long, though, so the project has not yet been put into action.

The European Parliament, the Council of the European Union, and the European Commission will need to adopt the text in the same terms. For now, the European Parliament has just reached a provisional agreement on the aforementioned regulation on April 27, 2023, which was voted on May 11, 2023. Once adopted, it will take some time before it comes into effect.

The proposed regulation focuses on transparency, accountability, and safety to promote the ethical and responsible development of AI within the European Union. The goal is to ensure trustworthy AI. The proposal includes a risk-based approach:

Unacceptable risks : AI systems that are prohibited because they contradict the values of the Union (e.g., facial recognition AI).

High-risk AI : These AI systems present risks to the health, safety, or fundamental rights of individuals (e.g., biometric identification AI). These systems are subject to strict obligations for developers, providers, and users.

Limited risks : Specific transparency obligations are established for these AI systems towards users. Users must be aware that when using AI systems such as Chatbots, they are interacting with a machine and must make an informed decision to proceed or not. As conversational agents are not categorised as high-risk AI systems, they will not be subject to the strict requirements applicable to high-risk systems.

Negligible risks : The proposal does not require intervention for these AI systems due to their minimal or non-existent risks to the rights or safety of citizens.

As mentioned earlier, the negotiating team of the European Parliament has reached a provisional agreement on the regulation, which includes generative AI (19). In this regard, “general-purpose AI systems,” capable of performing multiple functions, are distinguished from “foundational models,” which are techniques based on a large amount of data and can be used for various tasks. Providers of such models, like OpenAI, would be subject to stricter obligations, including the adoption of risk management strategies and ensuring the quality of their data.

The European Parliament announced in a press release (20) that the Members of the European Parliament have adopted the negotiation mandate project. This project still needs to be approved by the entire Parliament in a vote scheduled for June 12th to 15th.

Furthermore, on September 28, 2022, the European Commission published two directive proposals aimed at establishing rules on liability adapted to AI systems. These directive proposals seek to evolve the law of civil liability for AI systems. However, neither of these proposals specifically addresses issues related to intellectual property infringement or the corresponding liability framework.

Proposal for a Directive on Liability for Defective Products

The European Commission proposes a revision of the directive on liability for defective products (21) to adapt it to technological developments in recent years. The aim is to overhaul Directive 85/374/EEC of July 25, 1985 (22).

This revision proposes several changes, including redefining the concept of a product, reevaluating the concept of damage, imposing requirements on companies to disclose certain information, and altering the burden of proof for victims, including the introduction of specific presumptions and apply to liability for defective products without restriction and cover products stemming from AI or any other product.

Proposal for a Directive on Liability in the Field of AI

The second proposal for an AI directive aims to align the rules of non-contractual civil liability with the field of AI (23). This proposal addresses legal uncertainties identified by the European Commission for businesses, users, and the internal market. Multiple factors present challenges, including the enactment of rules of civil liability, the identification of the party responsible for the damage, the establishment of evidence, and the risk of fragmentation concerning applicable legislation.

The Commission’s cautious approach is demonstrated by provisions that shift the burden of proof in favour of victims of AI-based products or services. As a result, victims will have the same level of protection and may be less discouraged from filing civil liability claims. Thus, civil actions based on fault for damages caused by AI systems can be facilitated.

The risks in terms of liability for the actors involved in these fields are high and require particular attention. The proposed regulation provides for the establishment of a deterrent sanction system. Indeed, any breach of the established rules may be subject to an administrative fine of up to 20 million euros, or 4% of the company’s total annual turnover.

Companies and AI system providers are advised to closely monitor legislative developments and comply with future regulatory requirements to avoid any litigation.

Conclusion

While many options are being considered to establish AI regulations, the contractual aspect should not be overlooked. Contracts can complement or compensate for deficiencies in the forthcoming legislative framework. By leveraging this tool, a comprehensive strategy can be devised to regulate the use of AI, its consequences, the dynamics among various stakeholders, individual responsibilities, and other relevant aspects.

As users of AI systems, it is important to take certain precautions. These include establishing an internal written policy, being well-informed about the terms of use of AI systems, avoiding the disclosure of confidential information during their use, and verifying the reliability of the information provided. The role of general terms and conditions is vital, as they offer valuable information, such as the applicable law and jurisdiction, the extent of the service provider’s liability, indemnification, and disclaimer clauses. As a result, AI providers must prioritise the careful drafting of these terms and conditions.

Further reading

Copyright in front of artificial intelligence

Can an Intellectual Property Lawyer Help Me with Copyright Infringement in the EU ?

References

- Parlement européen. Intelligence artificielle : définition et utilisation | Actualité. 9 juillet 2020. URL : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/fr/headlines/society/20200827STO85804/intelligence-artificielle-definition-et-utilisation

- CJCE, 16 juill. 2009, aff. C-5/08, Infopaq

- CJUE, 11 juin 2020, aff. C-833/18, Brompton

- CJUE, 1er déc. 2011, aff. C-145/10, Eva-Maria Painer

- Dreyfus, N. [Chine] Le droit d’auteur à l’épreuve de l’intelligence artificielle. Village de la Justice. 1e décembre 2021.

- United States Copyright Office, Zarya of the Daws (Registration #VAu001480196), 21 février 2023.

- Rapport du CSPLA. Mission intelligence artificielle et culture. 27 février 2020.

- Proposition de règlement du Parlement européen et du Conseil établissant des règles harmonisées concernant l’intelligence artificielle (législation sur l’intelligence artificielle) et modifiant certains actes législatifs de l’union, Commission européenne, 21 avril 2021, COM/2021/206 final.

- Coles, C. 11 % of data employees paste into ChatGPT is confidential – Cyberhaven. 21 avril 2023. URL : https://www.cyberhaven.com/blog/4-2-of-workers-have-pasted-company-data-into-chatgpt/

- Commissariat à la protection de la vie privée du Canada. Le Commissariat ouvre une enquête sur ChatGPT. 4 avril 2023. URL : https://www.priv.gc.ca/fr/nouvelles-du-commissariat/nouvelles-et-annonces/2023/an_230404/

- Garante Per la protezione dei dati personali. Intelligenza artificiale : il Garante blocca ChatGPT. Raccolta illecita di dati personali. Assenza di sistemi per la verifica dell’età dei minori. 31 marzo 2023. URL :https://www.garanteprivacy.it/web/guest/home/docweb/-/docweb-display/docweb/9870847

- CNIL. Chatbots : les conseils de la CNIL pour respecter les droits des personnes. 19 février 2021. URL :https://www.cnil.fr/fr/chatbots-les-conseils-de-la-cnil-pour-respecter-les-droits-des-personnes#:~:text=Une%20telle%20action%20est%20encadr%C3%A9e,%C3%A0%20l’activation%20du%20chatbot.

- CNIL. Lignes directrices et recommandations de la CNIL. URL :https://www.cnil.fr/fr/decisions/lignes-directrices-recommandations-CNIL

- Article 82 de la loi n° 78-17 du 6 janvier 1978 relative à l’informatique, aux fichiers et aux libertés, modifiée par Ordonnance n°2018-1125 du 12 décembre 2018 – art. 1

- Directive 2002/58/CE du Parlement européen et du Conseil du 12 juillet 2002 concernant le traitement des données à caractère personnel et la protection de la vie privée dans le secteur des communications électroniques (directive vie privée et communications électroniques)

- Règlement (UE) 2016/679 du Parlement européen et du Conseil du 27 avril 2016, relatif à la protection des personnes physiques à l’égard du traitement des données à caractère personnel et à la libre circulation de ces données, et abrogeant la directive 95/46/CE (règlement général sur la protection des données).

- Résolution du Parlement européen du 20 oct. 2020 (2020/2012(INL)) ; (2020/2015(INI)) ; (2020/2014(INL)) ; Résolution du Parlement européen du 19 mai.2021 (2020/2017(INI)) ; Résolution du Parlement européen du 6 oct. 2021 (2020/2016((INI)) ; Résolution du Parlement européen du 3 mai. 2022 (2020/2266(INI))

- Proposition de règlement du Parlement européen et du Conseil établissant des règles harmonisées concernant l’intelligence artificielle (législation sur l’intelligence artificielle) et modifiant certains actes législatifs de l’union, Commission européenne, 21 avril 2021, COM/2021/206 final.

- Sophie Petitjean, Le Parlement enfin prêt à voter sur le règlement pour l’IA, Contexte Numérique, 27 avril 2023. URL : https://www.contexte.com/article/numerique/le-parlement-enfin-pret-a-voter-sur-le-reglement-pour-lia_167920.html

- Parlement européen, Un pas de plus vers les premières règles sur l’intelligence artificielle, Actualité, 5 nov. 2023. URL : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/fr/press-room/20230505IPR84904/un-pas-de-plus-vers-les-premieres-regles-sur-l-intelligence-artificielle

- Proposition de directive du Parlement européen et du Conseil relative à la responsabilité du fait des produits défectueux, COM (2022) 495 final, 28 sept. 2022

- Directive 85/374/CEE du Conseil du 25 juillet 1985 relative au rapprochement des dispositions législatives, réglementaires et administratives des États membres en matière de responsabilité du fait des produits défectueux

- Proposition de directive du Parlement européen et du Conseil, COM (2022) 496 final, 28 sept. 2022

Introduction

Introduction

Customs seizures of counterfeit goods increased significantly in 2022. While French customs intercepted 5.6 million counterfeit items in 2020, seizures increased to 11 million in 2022. On February 23, 2023, the Ministry of Public Accounts stated, “Counterfeiting no longer spares any sector of the economy1.”

Customs seizures of counterfeit goods increased significantly in 2022. While French customs intercepted 5.6 million counterfeit items in 2020, seizures increased to 11 million in 2022. On February 23, 2023, the Ministry of Public Accounts stated, “Counterfeiting no longer spares any sector of the economy1.”

In response to the digital age’s demand for creativity and innovation, the European Union has recommended a

In response to the digital age’s demand for creativity and innovation, the European Union has recommended a

In a world where the lines between different artistic disciplines are becoming increasingly blurred, fashion designers often draw inspiration from art to bring their collections to life or to promote their brands.

In a world where the lines between different artistic disciplines are becoming increasingly blurred, fashion designers often draw inspiration from art to bring their collections to life or to promote their brands.

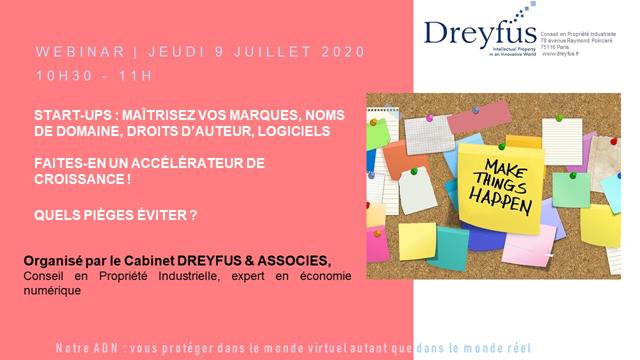

The French Public Investment Bank (BPI France) has set up a program to help SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises) and ETIs (Ethical Trading Initiatives and mid-sized companies) who are seeking or looking for help in developing and structuring their intangible assets. These intangible assets include patents, designs, trademarks and software.

The French Public Investment Bank (BPI France) has set up a program to help SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises) and ETIs (Ethical Trading Initiatives and mid-sized companies) who are seeking or looking for help in developing and structuring their intangible assets. These intangible assets include patents, designs, trademarks and software.

Webinar start up on July 9, 2020 :

Webinar start up on July 9, 2020 :